The traditional weapons used in wushu were originally derived from the weapons of ancient China. They can be categorized as follows:

- Short Weapons: various swords (broadswords and straight swords), daggers, axes, and hammers

- Long Weapons: staff, mace, spear, trident, long-handled axes, and halberds

- Soft Weapons: rope dart, chain whip, meteor hammer, and three-section staff

The four major weapons of wushu include:

- Staff (棍, gùn)

- Spear (槍, qiāng)

- Straight sword (劍, jiàn)

- Broadsword, also called a sabre (刀, dāo)

Other commonly practiced weapons include the three-section staff (三節棍, sānjié gùn) and 9-section whip (九節鞭, jiǔ jié biān), also called a chain whip. Some weapons are practiced in double-forms (one in each hand), such as double broadsword, double straight sword, and double chain whip.

Almost every weapon has multiple variations. For example, 棒 (bàng) is a short staff, also called a whip staff. The straight sword is sometimes practiced with a long, trailing tassel, and is rightly called a long-tasseled sword (長穗劍, zhǎng suì jiàn).

Staff (棍, gùn)

The gùn is typically made from wax wood or rattan. These woods are strong, light, and flexible. Newer versions are also made from other lightweight materials, such carbon fiber. The staff is about the same height as the user (or an inch or two taller). It is typically tapered, thicker at the base and thinner at the top. Gùn are considered one of the oldest weapons, used throughout Asia as long as there has been recorded history. It is said in some traditions that monks – after studying basics for one year – were taught gùn to protect the monastery.

Three-Section Staff (三節棍, sānjié gùn)

Sānjié gùn have properties from all three weapon types. When the ends are wielded in each hand, it behaves like a pair of eskrima (short fighting sticks). When handled from the center section, it has many movements in common with a traditional gùn. And when handled from one of the ends, it is more like a soft weapon in its flexibility and length. Sānjié gùn – like their single-piece cousin – are often made from wax wood, but are also made from metals and carbon fiber. Each section is about 2′ in length, with a short chain attaching the ends. The flexibility of sānjié gùn make it difficult to master, as timing and understanding of the weapons reactions to movement are critical. However, unlike other solid weapons (such as the gùn), practitioners tend to know quickly if they are doing something wrong, as it often results in injury. These painful lessons reduce the chances of building bad habits or using improper techniques.

Staight Sword (劍, jiàn)

The history of the jiàn dates back over 2,500 years. In modern times it is used by both wushu and taijiquan practitioners. The jiàn is a double-edged straight sword, averaging 28″ in length. The hilt is straight, and has a cross-guard with short wings (pointed either forward or backward). The pommel of the jiàn is weighted for balance, and some pommels have tassels attached. The blade itself typically has a very gentle taper at the end, and is about half the thickness at the tip of the blade as at the root. The jiàn was originally a military weapon, but was replaced by the dāo during the Han Dynasty. Today’s modern jiàn use much thinner blades which are much lighter and more flexible than their battle-wielded counterparts. A variation of the jiàn is the zhǎng suì jiàn (長穗劍), or long-tasseled sword.

Broadsword / Saber (刀, dāo)

The broadsword or saber is a single-edged sword, with a moderately curved blade. The moderate curve allows for thrusting as well as slashing. The hilt of the sword often curves in the opposite direction, of the blade to improve handling, and is topped by a circular cross-guard. Sometimes the hilts will also include lanyards or scarves. The term dāo literally means “knife”, and is generally used in reference to any single-edged blade.

The earliest records of dāo are from China’s Bronze Age, during the Shang Dynasty. Though the jiàn (straight sword) was a more common military weapon at the time, the dāo became popular during the Han Dynasty, used by cavalry. It was preferred because of its ease-of-use in comparison to the jiàn or qiāng (spear), and would later replace the jiàn almost completely within the military.

Some variations on the dāo include:

- Yàn máo dāo (雁毛刀): goose-quill saber

- Liǔyè dāo (柳葉刀): willow leaf saber

- Niúwěi dāo (牛尾刀): Ox-tailed sword

- Pǔ dāo (樸刀): polearm weapon with a sabre-style blade

Spear (槍, qiāng)

Like the gùn, the qiāng is a weapon found in many cultures, and due to its relative simplicity in construction was used extensively in ancient China as a military weapon. The blade of the spear is leaf-shaped, and usually has red horse-hair tassel hanging just below the spearhead. The tassel severed several purposes:

- A designation of elite troop status

- It served to disguise the movement of the spearhead, making it difficult to track and/or grasp

- Some claim it helped stop blood from running down the shaft of the spear

Military qiāng were made of hard woods and metals, though modern spears are usually made from wax wood as they are lighter and more flexible. Qqiāng and gùn share many of the same characteristics and movements, though qiāng are typically longer than gùn.

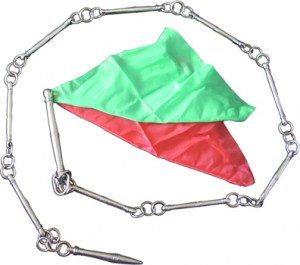

Chain Whip (鞭, biān)

The most common of the biān is the jiǔ jié biān (九節鞭), or nine-section whip. This consists of a small, metal or wood handle (sometimes wrapped in leather or wood), solid metal sections connected by small rings (varying typically from seven to thirteen sections), and a heavy metal dart (sometimes pointed). Flags are often added to the rings that connect to the dart. The flags add stability, slowing the movement of the dart and making it move more predictably. They also add a rushing sound as well as visibility, enhancing demonstrations. The jiǔ jié biān was first used in battle during the Jin Dynasty, some 1,800 years ago. The many links allow the whip to strike around objects, and it’s flexibility allows it to be easily concealed. The weighted dart at the end of approx. 6′ of chain links allows for very high rotational speeds, making this a devastating weapon in the hands of a skilled practitioner, and a very dangerous weapon in the hands of a foolish novice.

Monk Staff (錫杖, xízhàng)

The monk staff is a mace-styled weapon with a long handle, and a large metallic head akin to a cage with several rings. This weapon originates from India, and was primarily used by Buddhists in prayers. The Sanskrit term for this weapon is khakkhara, which means “sounding staff”. The rings were meant to ward off insects and small creatures so as to not be accidentally stepped on. The number of rings on the staff have various representations:

- Four rings: Four Noble Truths

- Six rings: Six Perfections

- Twelve rings: Twelvefold Nidānas (chain of cause and effect)

The monk staff has been used for defense by traveling Buddhist monks all over Asia, and monks at the Shaolin temple in China specialize in its use.

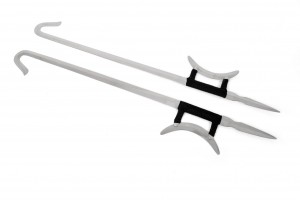

Double Hook Sword (双鉤, shuāng gōu)

Though it is claimed the hook swords are among the ancient Chinese weapons dating back to the Song Dynasty, most examples come from the Qing Dynasty or later. They were not very common, and were not listed among official Chinese armaments (not used within the military).

Hook swords have five distinguishing features:

- The end of the hilt is sharpened

- The sword ends in a hook, which can slash and catch weapons

- The guard around the hilt is a crescent, also sharpened

- The straight portion, which is a standard, double-edged straight sword (like jiàn)

- Hook swords can be linked, allowing one sword to be held while the other is swung towards the enemy

Read more on double hook swords.

Polearm (樸刀, pǔdāo)

Pǔdāo is a pole weapon or pole arm, where a dāo-style blade is fixed to the end of a long shaft, typically wood. The shaft is approximately 4-6′ in length, with a circular cross-guard between the shaft and the blade. It has a similar look to yǎnyuèdāo (偃月刀) or “reclining moon blade” which – unlike pǔdāo – has a spike at the back of the black and sometimes includes a notch at the spike’s upper based to catch weapons. Pǔdāo is sometimes called “horse cutter” or “horse chopper” as it was speculated that the weapon was used to slice the legs from horses during battle. However, this should not be confused with the zhǎn mǎdāo (斬馬刀), literally “horse chopping sword” which was a long, curbed, single-edged anti-cavalry sword using during the Song Dynasty.

Halberd (戟, jǐ)

Jǐ – initially a cross between the qiāng (槍, spear) and gē (戈, dagger-axe) – are originally military weapons in use from the early Shang dynasty to the end of the Qing dynasty. They were used by infantry, cavalry, and charioteers. There are many varieties of jǐ. Sometimes the blade is serrated, other times it is crescent-shaped, and stillk others are far more elaborately designed. Some jǐ have blades on both sides of the shaft (double-bladed).

Because of the weight of the blade(s) at the end of the jǐ, it is often counter weighted at the based of the shaft, allowing for strikes at this end as well.

Polearms (such as pǔdāo) and battleaxes (鉞, yuè) are often mistaken as jǐ.

Hammer (錘. chuí)

Chuí are melee weapons made from a medium-length handle attached to a large, solid metal sphere. Due to the distal nature of the sphere – and the sheer weight – these weapons require a considerable amount of strength to wield properly. Modern versions often have hollow spheres to make them easier to handle, though removing their practicality as a combat weapon. Chuí – when practiced, though they are not commonly taught in modern times – are almost always used in pairs.

Meteor hammer (流星錘. liúxīng chuí)

A variant of chuí, liúxīng chuí uses two spherical weights attached to one another via a rope or chain, typically 4-6′ in length. There are also single-headed versions of liúxīng chuí as well, which operate similar to jiǔ jié biān or shéng biāo (繩鏢, “rope dart”). Practice versions are typically made of thick rope, with a monkey’s fist knot at either end of the rope.